On the Back of a Huntsman is a text based artwork written to be performed as a guided tour. It was written for The Timeline exhibition of Nationalmuseum and evolves around the experiences of the non-human animals inhabiting five of the paintings that can be seen in the exhibition. The text was performed at Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, Sweden, on January 30th 2019.

The text brings forward the imagined experiences and dreams of the non-human animals portrayed by the five paintings, centering on a less anthropocentric version of art history while using anthropomorphism and empathy as methods to imagine these new experiences.

What is it like to be part of the history of art and its production system of oppression and violence? What happens if we refuse to read the once living symbolically and instead recognise agency?

•

On the Back of a Huntsman belongs to one of the chapters of my phd project together with two more chapters of guided tours titled Green Feathers and The We and I of the Bishop’s House. On the Back of a Huntsman was made in collaboration with Nationalmuseum and Konstfack Research Week and partially funded by Konstnärsnämnden through a project grant.

These are the five following paintings that the work is based on:

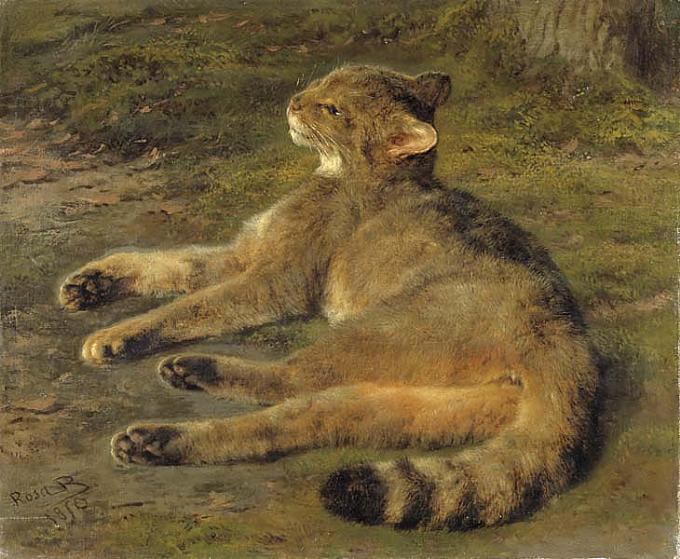

Wild Cat 1850 by Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

Peasant Girl Milking a Cow 1659 by Karel Dujardin (1626-1678)

Murmeldjur n.d by David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl (1628-1698)

White Squirrel in a Landscape 1697 by David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl (1628-1698)

Bringing Home the Body of King Karl XII of Sweden 1884 by Gustaf Cederström

•

Here follows a couple of images documenting the tour at Nationalmuseum on January 30 2019 as well as an excerpt from the text of the capercaille of Gustaf Cederström.

↓

An excerpt from

BRINGING HOME THE BODY OF KING KARL XII OF SWEDEN

Nationalmuseum, fourth floor

The artist is standing infront of the painting. The audience is gathered in a semicircle facing the painting. The artist reads:

Follow the wind and you will find me. The icy cold wind whips the royal standard forcing the soldier carrying the flag to struggle, holding hard with both hands. The wind lifts his coat, hurrying on, almost catching the hat of another soldier before grabbing his coat, turning it into life. Then suddenly, the wind is pushed to the ground carrying snow over the ledge pushing snow behind the golden frame and out of reach of this painting. And there you have me. In front of the snow falling over the ledge, on the back of the huntsman. Hanging upside down with my head dangling towards the humans back side. Blood dripping from my beak, leaving a small trace of red in the snow-filled footprint of the human who killed me. Here I am. And I refuse to be read symbolically.

I am what Carl Linnaeus defined as TETRAO UROGALIUS. You call me capercaillie, wood grouse or as they say in the province of Jämtland: tjäder, gråfågel or fjärrhane. Whether my name is given me in relation to the colors of my feathers or because of the relation to other birds in a never-ending organization of all that is living, the names control me.

I find myself within the golden frames of this painting by Gustaf Cederström from 1884, but you can also find me in an earlier version from 1878. Both paintings are named Bringing Home the Body of King Charles the twelfth of Sweden.

Just as there are two physical representations of me there are two ways for you to see and read my presence: Either as a symbol or as a once living being. I refuse to think of myself as a symbol, and therefore urge you to read me as living. Because once I was alive. Or once someone was alive for someone else to kill and later study. Humans wants other animals to be still so that they can study. So that you can create a perfect watercolor drawing of the back feathers of someone like me. And it takes several. I am not only one. I am a series of me. I am an US.

The artist used his brother, colleagues, friends, and his child to stand as models for some of the painted humans, but to be able to paint us he had to study one of our kind, hanging upside down. To paint us we had to be killed.

Not long ago we were moved from the stair halls of this museum …